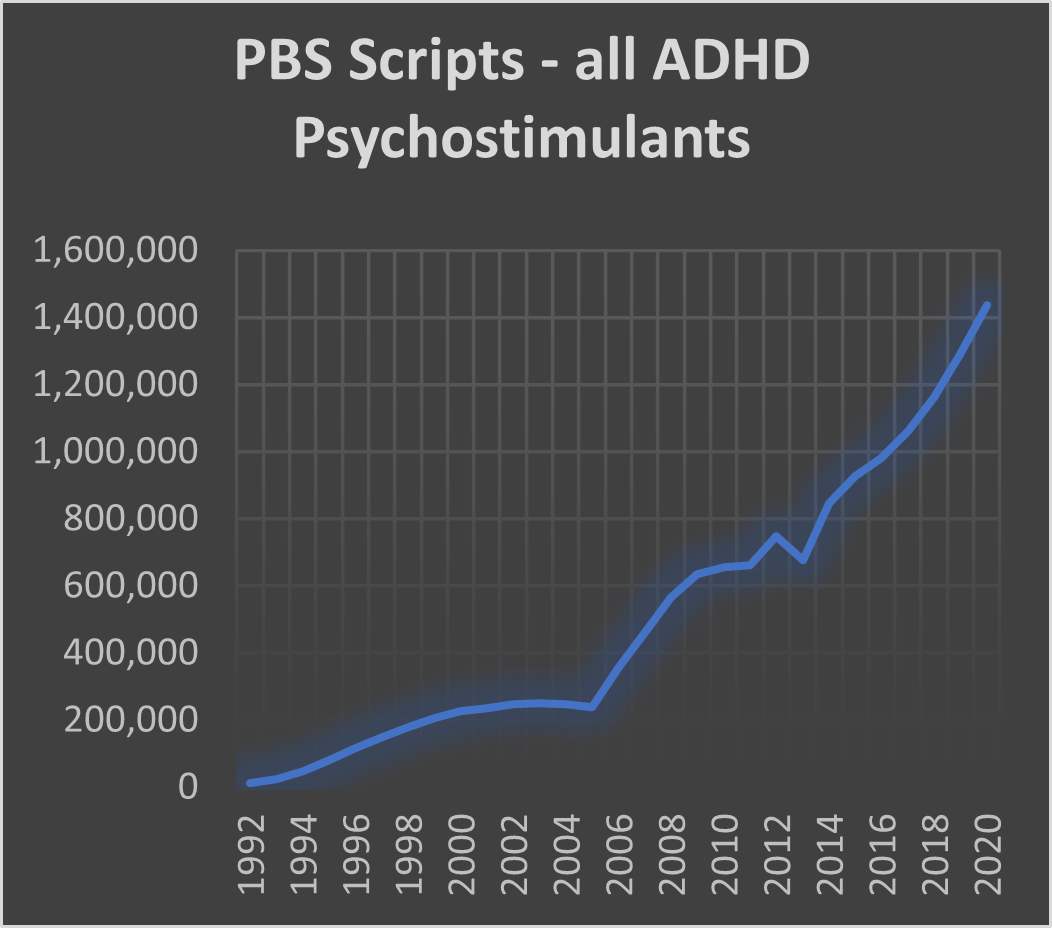

In December 2018, the Australian Human Right’s Commission reported to the UN that “Australian is among the countries with the highest rate of ADHD diagnosis in the world for children 5-14 years, and the number of psychostimulant drugs prescriptions has increased dramatically.” In the two short years since then, Australia has increased the prescription of these drugs by a 24 percent.

In 2020 the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) subsidised almost 1.5 million prescriptions for ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) medication. That is double what it was just 8 years ago and is ten times the number from 1997. We don’t have accurate current Australian statistics on ADHD but if the rate of growth in prescription drugs is any kind of guide, we have a very big problem, and it is growing at more than 10% a year.

ADHD is a neurological disorder defined by symptoms. People with ADHD are inattentive, impulsive, and in some cases, hyperactive. The primary driver of those symptoms is an inability to focus. In boys this often manifests as disruptive behaviour and in girls as inattentiveness.

Our ability to ‘focus’ is dependent on dopamine, a critical part of our reward system. It keeps us focused on chasing rewards and when there is danger, focuses us on avoiding it. Even when rewards or danger are not in play, we keep our mind on the job with dopamine.

Like all mental illness, ADHD is likely attributable to an underlying propensity, but stress and addiction can significantly increase the likelihood of symptoms developing. The figures make it clear that we are creating disease. When we experience chronic stress due to uncertain housing, food insecurity or violence, for example we develop a tolerance to dopamine by increasing the baseline levels we need to focus. The same thing happens when we become addicted to things like sugar, online games, social media, porn, alcohol or other drugs. When our brain is in that dopamine-adapted state, our dopamine levels are too low when we are not doing something addictive.

When dopamine levels are too low, we can’t focus. Our mind feels like it is running too fast, and we struggle to hold a thought for more than a few seconds. This is how addiction and stress leads directly to ADHD behaviour and it is why most people who are diagnosed with the condition are addicted or stressed or both. This rewired state also downgrades our impulse control. The net effect is that we have random and rapidly changing impulses and are more likely to act on them.

ADHD and classroom education mix about as well as oil and water. Kids with ADHD are often compelled to move constantly, are easily distracted by noises or sights in or near the classroom, will frequently interrupt teachers and other students, struggle to translate learning into understanding and have trouble paying attention. It is challenge for educators to remember that none of this behaviour is voluntary and not punish the child or demand that they be medicated.

The drugs dispensed at an increasingly frenetic rate to ADHD sufferers are dopamine stimulants. Just like any stimulant drug, they help us keep focus. Their mechanism of action is similar to cocaine and amphetamines. They don’t do anything about the cause of the low dopamine state but, for as long as we take them, they can usually stimulate enough dopamine to stop our mind wandering off task. They can of course be highly addictive. This is why the World Health Organisation (WHO) has refused to add them to its list of effective and safe medicines. Yes, that’s right, the current ‘cure’ for lack of focus driven by addiction (or stress or both) it to give children addictive drugs which the WHO has refused to recommend.

As distressing as those numbers are, it’s worth remembering that ADHD medication prescriptions have doubled since that data was collected, so they are likely to be a significant underestimate. Those same medication numbers tell us that just two decades ago ADHD was a tenth of the problem it is now. In other words, encountering a child with ADHD in the average classroom was a rare event. The way the numbers are going, within 10 years it will be rare to encounter a child without ADHD.

We are on a fast track to having a generation of kids who are impossible to educate unless they are taking potentially addictive stimulants that predispose them to a life of addiction. If you think that’s an exaggeration, take another look at the graph. ADHD is a problem with a rocket and the current ‘solution’ is ignite the afterburner. We need a plan that supports parents, reassures educators, and helps kids. We need a plan that fixes the root causes, addiction and financial insecurity. And we need that plan yesterday.

Photo by Tara Winstead from Pexels

Recent Comments