SHE would probably have been less shocked had I confessed to selling my children into slavery.

The look of horror (with a tinge of outrage) said a truckload more than the “Oh, are you sure?” she finally managed to squeeze out. Nigella (name changed) is the proud mother of two kids who attended the same (government) preschool as our eldest and had then progressed to the same (government) primary school. At Year 4, she had shipped her children off to the most prestigious private boys’ and girls’ schools money could buy (in Brisbane). So when I announced that my wife Lizzie and I had decided our kids would be going to a government high school, the shock was palpable. “But,” she spluttered, “didn’t you go to Churchie? Surely you could get them in there as a legacy entry?” The idea that anyone might choose to have their kids educated in a public school seemed to be beyond any reasonable contemplation.

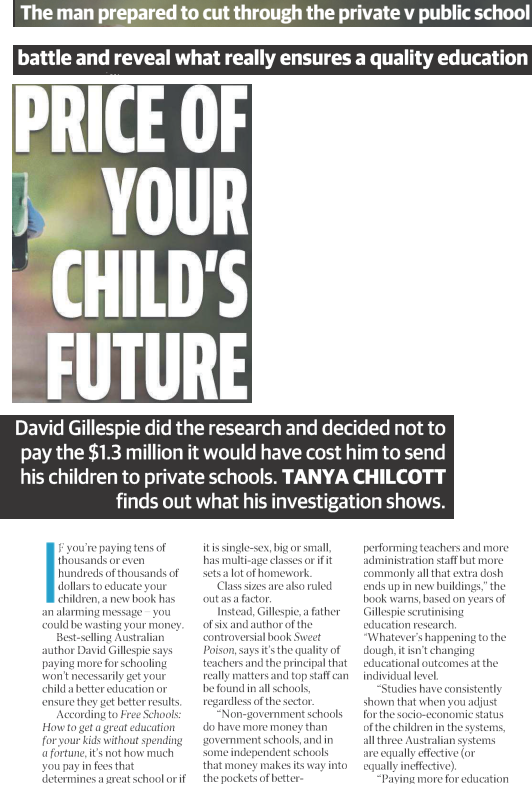

If people voting with their feet is any measure, Nigella speaks for the majority. In some Australian urban areas there are now more Year 11 and 12 children in private education than there are in state schools. But is it really the case that paying for education actually gets you a better result? Or that paying even more gets an even better result?

We have six kids, so the kind of eye-watering numbers that the automatic choice of sending them to my alma mater and its sister school implied ($1.3 million, I calculated) meant our kids were going public. I needed to know exactly what the research said about educational outcomes and money. And I really needed to know whether there were any smart choices I could make having decided on public education.

Much like medical research, educational research is arcane, hard to read and even harder to understand. Even worse, most of it appears to be based on hunches and feelings and very little of it on hard facts and actual trials. But once you strip away all the self-interest and the spin there are very clear messages about why some education systems and schools perform better than others.

The research tells us there’s no correlation between how much you pay and the quality of the education your child is likely to receive. Parents desperate to escape a system that refuses to remove (and indeed actively protects) poorly performing teachers are susceptible to the promise of better results if only they can pay for them. The wealthiest families dominate the independent schools, which draw almost half their population from the top quarter of income earners in Australia and 73 per cent of their students from the top half of the income scale. Government school students dominate at the lower end of the economic spectrum; these schools draw 36 per cent of their students from the lowest quarter of Australian incomes. Catholic schools are somewhat more balanced; 57 per cent of their students come from the top half of the income scale.

Non-government schools do have more money than government schools, and in some independent schools that money makes its way into the pockets of better-performing teachers and more administration staff, but more commonly all that extra dosh just ends up in new buildings. Studies have consistently shown that when you adjust for the socioeconomic status of the children in the systems, all three Australian systems are equally effective (or ineffective). Paying more for education will definitely get you nicer buildings and newer computers. And it will definitely allow your child to hang around with more kids of “his class” (assuming that’s a benefit).

The single advantage that independent schools have over government and Catholic schools is that their staffing policies are not dictated by union-negotiated enterprise agreements. The principal of an independent school has much greater power to remove underperforming staff and hire effective teachers than their colleagues in either the government or Catholic sectors. But a leader is no more likely to employ and develop effective staff if they themselves are incompetent or if their hands are tied by a board (or parents) dictating staffing policies (as often happens). Yes, they may be able to have better staff, but that’s no guarantee that they do.

The short way of saying this is that paying for an education is often unlikely to get you a better academic result than you’d get anyway. What I found during my research is that some things – teachers, principals – count a lot, while other things that most parents worry about – class size, school size, composite classes, fancy buildings – don’t matter at all.

Teachers and leaders matter

Good teachers get good results (significant and measurable gains in the academic performance of their students). Poor teachers achieve exactly the opposite. In one Queensland study, the quality of the teacher was shown to matter to the tune of an astounding full academic year’s worth of learning when you compare the best teachers with the worst.

Researchers involved in The Texas Teacher Quality Study found that teachers at the top of the quality distribution were able to move their students forward one and a half years in just a year, while the worst teachers were only able to move their kids forward half a year. The study also found that experience makes a difference, at least initially. Teachers who are new in the job are much less effective. But after three years, experience doesn’t appear to affect teacher performance at all.

Until recently we haven’t had any comparable research on teacher effectiveness in Australia, but in 2010, Andrew Leigh (formerly a statistician from the Australian National University and now a member of federal parliament) completed a major study of teacher effectiveness using the standardised test scores for 90,000 Queensland students between 2001 and 2004. The results were almost identical to those delivered by the US research. A teacher who’s better than 90 per cent of their peers will achieve in six months what a teacher in the bottom 10 per cent achieves in a full year.

And this doesn’t apply just to primary school. A large study in Chicago showed the effect was, if anything, more pronounced in high school teachers. Good teachers eliminate disadvantage. In comparison to a bad teacher, a good teacher will provide your child with a two-for-one deal: two years of education in a year. If they get two shockers in a row they’re on a path to academic destruction.

It doesn’t matter if the school is mixed or single-sex

I don’t know a parent who doesn’t have a view on whether schools should be single-sex or mixed. The demand for single-sex schooling appears to persist despite a spectacular lack of evidence that it makes the slightest bit of difference for either sex. In 2005, the US Department of Education conducted a systematic review of 2221 studies on single-sex education. They found a performance gap between single- sex schools (and classes) and coeducational schools, but that gap could be explained entirely by the differences in the socioeconomic make-up of the students likely to attend a single-sex school (which in the United States are usually private). When the researchers looked for longer term measures of success, any positive effects of single-sex schooling vanished entirely. Without even adjusting for background, they found no differences in academic performance beyond high school, university graduation rates or the likelihood of undertaking postgraduate study.

Closer to home, the WA Education Department reviewed the inconclusive evidence and decided to find out if it could detect a measurable benefit by trying single-sex classes in its high schools. The pilot program was implemented in five public high schools commencing in 2006, but after three years of trials in Years 8 to 10 classrooms, they found there was “no conclusive evidence in any school to indicate that single gender classrooms supported improved student outcomes”.

Composite classes don’t matter

Multi-age classes mix students of more than one (usually two, but sometimes more) grades in one classroom being taught by one teacher. They’re fairly common in small schools (less than 200 students – just under half of all Australian primary schools) because of uneven distribution of the numbers of children in each grade and the need to stay below the mandated upper limits on class size. Most parents I’ve met think multi-age classes are a good idea if their child is one of the youngest in the class but a bad idea if they’re one of the older kids. The resounding answer from the research community is that it makes not the slightest jot of difference. Not only does multi-grading not have any positive or negative effect on academic performance, it doesn’t change any of the “soft” measures either (like attitude to school, behaviour and so on).

The Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) ran a study which was extraordinarily detailed and allowed the researchers to answer a burning question most of the previous studies hadn’t: Does it matter if your little pumpkin is in the Year 4 end of a 3-4 or in the Year 3 end? Not a single one of any of the possible combinations (and they had them all) showed any difference at all. The research did reveal, however, that some principals may have a tendency to assign their best and brightest teaching staff to multi-age classes.

Homework doesn’t make a lot of difference

When you’re dragging six kids through the school system you get to attend your fair share of parent meetings. And I reckon I haven’t been to one yet when someone didn’t complain that insufficient homework was being given, followed quickly by someone else complaining that too much was being handed out. Because it’s such a focus for parental angst, there’s no shortage of research on every conceivable aspect of doing schoolwork at home. But the research in favour of homework is far from convincing, and the latest work suggests it’s a complete waste of everybody’s time.

In 2006, Harris Cooper, the director of Duke University’s Program in Education in North Carolina, led a team that analysed the vast majority of the homework studies performed to that point. The studies revealed that there’s no benefit to assigning homework to children in years equivalent to Australian primary schools. Indeed, no study has ever found a benefit to assigning homework to children of that age. There were, however, modest benefits to high school students in that those who did more homework tended to score better on standardised tests. Even the most persuasive studies are only demonstrating a mild effect and then only really in maths.

Try hard to avoid moving

Australia has one of the most highly mobile populations in the Western world. The Australian Bureau of Statistics estimates that 30 per cent of residents (from households with children) move at least once every three years. The Queensland Department of Education keeps detailed records on every student and (uniquely in Australia) can track them no matter which school they attend. Their most recent analysis reported that, of the 41,261 students enrolled in Year 7 in 2006, one in five had moved schools two or more times in primary school and one in 20 had moved four or more times (in six years). The researchers concluded that the best thing we can do for our kids is keep them in the same school. The children who obtained the best results were those who hadn’t changed schools at all, and there was a direct relationship between (lack of) performance and the number of moves. In the last three decades there have been more than 40 major studies on the issue. The results have been surprisingly consistent. Every time a child is moved, their education will be set back between three and four months, their reading and maths scores will decline, and they’ll struggle to keep pace with their peer group.

The perfect school

The research tells us what a perfect school should be. It also tells us what it won’t be, or, at the very least, helps us identify all the red herrings hung along the school fence. It might have gorgeous grounds, three Olympic-sized swimming pools, its own personal sports stadium, a single sex, fabulous tertiary entry results, new computers, high fees, very small class sizes, and be very small and have no multi-age classes. But it might have none of those things and still be an extraordinary performer when it comes to delivering the only thing that matters – a high-quality education for your child.

The perfect school will have a highly effective leader who engages the community and teachers, who mentors those teachers and gets the best from them. It will have a teaching culture of continuous learning. Teachers will approach their task not as underpaid, glorified child care but as an opportunity to improve their skills and their students’ outcomes. And the perfect school may do absolutely nothing else. It may accomplish these two things in a caravan on a mining site, in a sandstone building on Sydney Harbour or in any possible location in between. What it looks like and what it costs are very likely to be completely irrelevant.

A truly extraordinary school will provide a music program and it will teach at least one foreign language. It will teach children how to learn rather than just what to learn. It will use technology to ensure students have immediate feedback and teachers have the time to help those who need it most. Homework won’t be a priority but the school will work very hard at keeping parents in the loop. It won’t stream students academically, but it will accelerate the truly gifted and will definitely not rely on whole language as a means of teaching literacy.

In other words, its perfection will be almost completely invisible to all but the participants. Its outcomes will in no way depend on the advantage or disadvantage the children bring through the school gate. All of this is quite easily delivered within the existing budgets for government school education (or less) if the school leader is skilled and motivated. They’re not the majority, but these schools do exist. The trick is to find them.

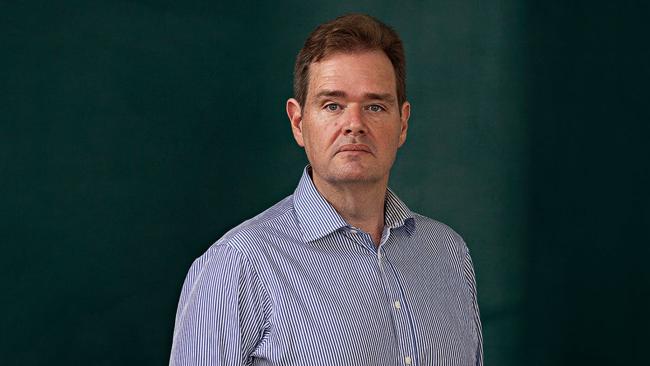

Edited extract from Free Schools: How to get your kids a great education without spending a fortune, by David Gillespie (Macmillan Australia, $29.99)

First Published in The Australian, 25 January 2014. Picture: Eddie Safarik Source: News Limited

Recent Comments