ACCORDING to international benchmarks such as the OECD’s Program for International Student Assessment tests, Australia’s education system is sliding backwards at a dizzying speed.

And while the research is unequivocal that teaching effectiveness is the primary driver of student performance, blaming teachers for the slide is like blaming an infantryman for the Iraq War. Band-Aids will not suffice. It’s time for open-heart surgery on Australia’s education system. Unfortunately, the Band-Aid brigade is out in force when it comes to “fixing” teacher quality. In Britain, the Conservative government plans to fix teacher quality by continuing to support Teach First. It is a social enterprise that enrols recent graduates from non-teaching courses and puts them through a six-week course before dropping them into a classroom while they complete a two-year education qualification.

The same program runs in Australia and the US, and while there are impressive queues of fabulous graduates waiting to join, the five-year retention rate for qualified teachers is abysmal – so much so that the program has been derided as “teach first, then get a better job”.

The British Labour opposition has a different plan. It wants to relicense teachers every few years. Its manifesto would allow the worst ones to be sacked and the not-so-terrible to receive some training. In the US, the Band-Aid contains a little more carrot and a little less stick. There, Bill Gates is pumping a lazy $US335 million ($384m) into a trial teacher incentive program. One of the trial districts, Hillsborough County (193,000 students and 15,000 teachers) in Florida received $US100m of the pile, and $US60m of that went directly to teachers. With the bonus payments, a fourth-year teacher in Hillsborough could earn as much as someone who’s been in the job for 20 years. The bonuses are based on student outcomes and in-class evaluations of teachers. But now that the trial results are in, they are not encouraging. There seemed to be no statistical relationship between any student improvement and the people identified by the program as effective teachers.

Elsewhere in the US, and most recently in NSW, “raising the bar” is seen as the panacea to ineffective teaching. People have been noticing for some time that it’s getting easier and easier to enrol in an undergraduate teaching degree. Latest results from Queensland, for example, tell us that entry is open to all but the lowest 8 per cent of secondary school leavers, and it isn’t much higher in NSW.

Statistics like that have inspired the NSW O’Farrell government to insist that, from next year, you don’t get to study teaching without at least an 80 per cent score in three HSC subjects (one of which must be English). It’s a big call with an almost complete lack of evidence to support it.

It’s not unreasonable to suggest we need moderately literate teachers, but study after study tells us that beyond that, there is no correlation between a teacher’s marks and their classroom results. Worse than that, it runs the real risk of excluding people who will be effective teachers on the basis of something that is likely to be about as relevant as their favourite colour. Unlike Britain and the US, the countries handing us a solid flogging in international tests (China, South Korea, Singapore and Finland, for example) are not worried about how to produce effective teachers, because they have already solved the problem.

The detail varies from place to place but the end result is the same. Effective teachers are produced by systems that use effective teachers to make more, you guessed it, effective teachers. In these systems, teachers are closely managed and mentored from the moment they darken a classroom doorway.

They are not thrown into a locked class, never to be seen again. They don’t sit down with the principal for a once-a-year box-ticking “performance review” (and then get a pay rise anyway). They are watched by their peers, assessed by more experienced colleagues and work as part of a team based on continuous feedback about the performance of their students. They can also be dismissed if they fail to deliver.

If they measure up, their career advancement is based on their performance (and that of their students), not on the amount of time in the job. And they are required to continue to learn and publish throughout their career. In other words, they are lifelong learners in the art and science of teaching. And they are trained by the best, the highest performers from the generations before them.

To someone who is “doing teaching” (because it’s easy to get into, with a pretty good graduate pay and great holidays), I have just described a nightmare of lifelong assessment. To someone who loves learning and loves teaching, I have just described paradise. Bring it on.

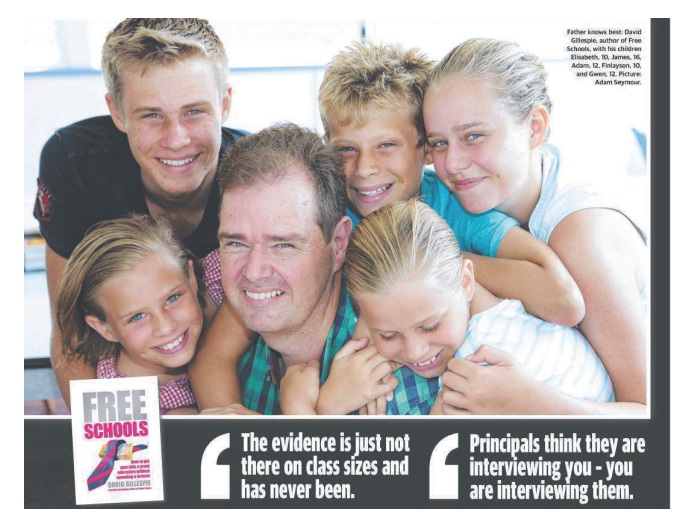

Opinion piece also published in The Australian 28 January 2014

David, I just chewed through Free Schools in the last 8 hours. As a student currently studying my Masters to become a primary school teacher, I’d like to thank you for your book. The doubts that I had about my ability to impact upon students in a system where I believe has so many faults in regards to resource allocation and funding have been quietened and replaced by hope and encouragement that my abilities and teaching are the greatest potential resource available to my future students. I am studying post-grad to become a teacher because I was discouraged from initially becoming a teacher as it is commonly looked down upon as a profession by many in my generation due to it’s limited earning capacity. It’s only taken me five years and your book to help me see that the professional satisfaction I crave will undoubtedly come from teaching, thank you.