Pre-covid, one in ten UK adults reported current symptoms of anxiety or depression. The number was similar in Australia and the US. By June 2020, the UK number had risen to one in five. By Christmas in the US 42% of all US adults were reporting the symptoms. There is no reason to believe Australia’s numbers will be any different when they are eventually published. The stress of covid and the lockdowns associated with it are driving mental illness to levels we have never measured or experienced before.

We also are starting to see similar increases in addiction and violent crime. A third of households now report drinking daily to cope with anxiety and one in five report buying more alcohol than usual. The number of Australians gambling four or more times a week increased by 40% during 2020. And according to crime data, assaults increased by 30% and domestic violence increased by 45%.

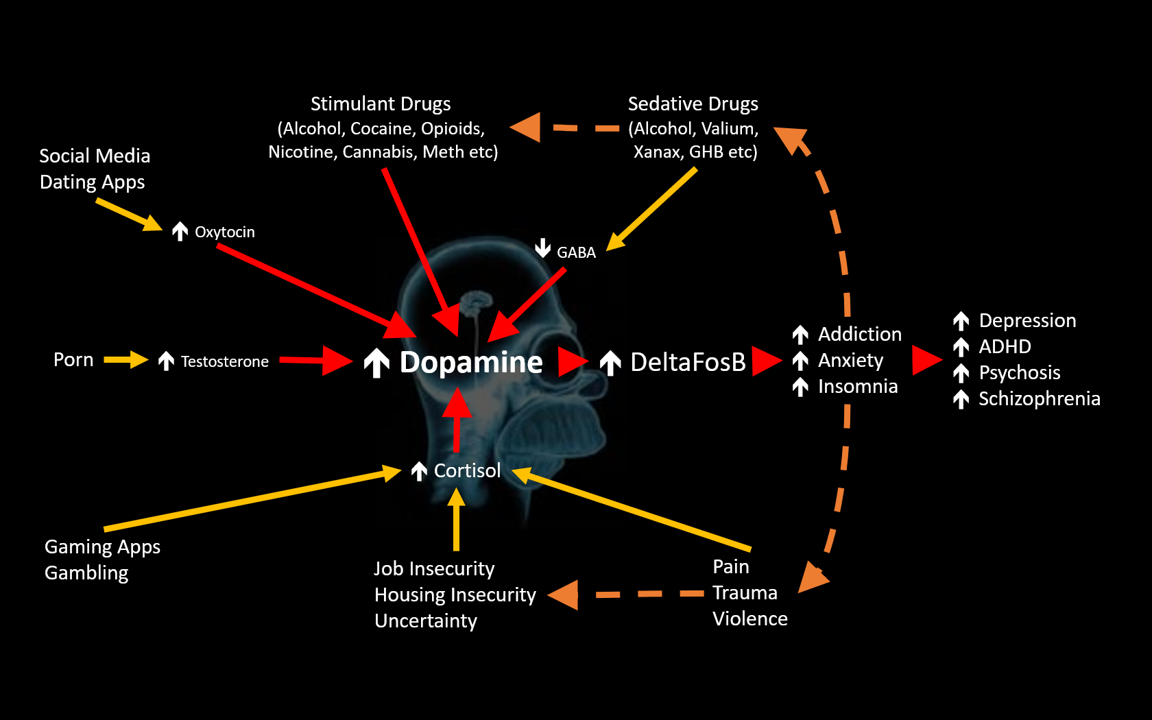

All of this is united by a single simple explanation that is based on the way our brain adapts to stress. The bad news is that this stress adaptation creates a self-perpetuating cycle that leads inevitably to addiction and mental illness. The good news is that we know this – and can stop it if we act quickly.

I live under a flight path. Visitors often remark about aircraft noise which I stopped noticing long ago. They live in quiet streets where a jet flying over at a thousand feet would stand out like canine gonads. But I have ‘backgrounded’ it because it happens to me every 10 minutes. That ability to not notice things which are part of our normal environment is an important survival mechanic. We need to be able to do that so that when something unusual happens we do notice it amongst the noise.

We don’t just do this for sounds. We do it for smell, colour, temperature, and pain to name just a few others. Critically we also do it for danger. If we live in a war zone, a stressful event like nearby gunfire will bother us a lot less than if we live in (say) Adelaide. In the war zone we would be adapted to the background of frequent gunfire so that we would react only to the noises which put us in real, imminent danger.

This response helps us cope with the ever-present risk so we can still function. If we responded to constant risk the way we respond to a once in a lifetime mortal threat, we’d be permanently frozen in fear. Our biochemistry changes the calculation of risk so we can keep moving forward even in the most hair-raising circumstances.

We do the same thing for rewarding behaviour. If rewards are rare, we keep a close eye out for them, but if we have unlimited access to reward, we get bored. We need more and more stimulation to manage the same level of desire. We create a new baseline for ‘normal’ levels of pleasure. Our brains background the good stuff just as efficiently as they do for the bad stuff. This is not particularly surprising because we use the same biochemistry for both.

The trap is of course that since both pleasure and pain trigger the same biochemical adaptation, they act as gateways to each other. People experiencing high levels of danger seek extraordinary levels of pleasure. And people experiencing high levels of pleasure accept significantly greater levels of danger.

But there is a bigger price to pay than merely seeking pleasure and danger. Because our brains have moved the goalposts on what is normal, we will overestimate the potential reward on offer – we call this addiction – and do the same for potential risk – we call this anxiety.

This is why, in times of chronic disease uncertainty, chronic housing insecurity and chronic job insecurity, we are seeing rates of addiction and mental illness skyrocket.

Worse, the adaptation to stress puts our brain in a state of impaired impulse control. We are more irritable, less able to make rational decisions and generally angrier and more impulsive. We might feel like punching the driver that just cut us off at the best of times, but when we are in this state we are much more likely to act on it. There is little wonder then that is exactly what we are seeing play out because of the stress associated with COVID and the government responses to it.

All hope is not lost, however. We can reset the brain wiring that holds us in a state of anxiety, addiction, and dangerous lack of self-control. It is not easy, but it is possible to reset our tolerance levels for danger and reward and return us to non-addicted, non-anxious equilibrium. Exactly how that is done is the subject of part two of this series.

Recent Comments