On the eve of the Great Depression, Dr Charles Bradley fresh out of his residency as a pediatrician took up the role of Medical Director at the Emma Pendleton Bradley Home for the treatment of children in Connecticut. The name wasn’t a coincidence. The Home had been established by a bequest from Bradley’s great uncle, George Bradley. George had made his fortune working with Alexander Graham Bell marketing the first telephones.

His beloved only child Emma had contracted encephalitis – a type of brain tissue inflammation causing intense headaches and seizures – when she was just seven. George and his wife, employed round-the-clock carers for Emma at their summer home while they travelled the world seeking treatment without success. When George died, his will contained provision for the creation of the Home using his Rhode Island estate (pictured). It was to become the first facility in the United States expressly designed to treat children with neurological and mental health disorders. An express provision of the will required that parents not be charged unless they could afford it.

His beloved only child Emma had contracted encephalitis – a type of brain tissue inflammation causing intense headaches and seizures – when she was just seven. George and his wife, employed round-the-clock carers for Emma at their summer home while they travelled the world seeking treatment without success. When George died, his will contained provision for the creation of the Home using his Rhode Island estate (pictured). It was to become the first facility in the United States expressly designed to treat children with neurological and mental health disorders. An express provision of the will required that parents not be charged unless they could afford it.

The Emma Pendleton Bradley Home treated a range of physical disabilities, but Charles Bradley focused on children with behavioral disorders. Those children usually came from distressed, often poor, families coping with serious drug or alcohol addiction and often extreme family violence. The Home had no shortage of patients in depression era New England. The children were highly reactive, oppositional, and refused to conform to ‘accepted social standards’ of behavior. The patients, whose hospitalization came as a relief to their families, were described as ‘inattentive, restless, rambunctious, and selfish.’

Bradley’s approach of getting the children away from their stressors and providing them with a stable home complete with access to extensive sporting facilities did have some success, but he was always on the lookout for ways to improve treatment.

In the mid thirties, American pharmaceutical company, Smith Kline and French (SKF – now GlaxoSmithKline) was scouting around for ways to increase revenue from its newly patented over the counter nasal decongestant Benzedrine. Benzedrine’s active ingredient was amphetamine, or what is today more commonly known as ‘speed’. SKF was keen to encourage trials to see if there was a bigger market for their drug than people with runny noses, so they offered free supplies to any doctor who agreed to conduct research. Speed worked as a decongestant because it constricted nasal mucus membranes. Bradley thought that membrane constricting effect might help with the intense headaches experienced by his patients because of a diagnostic procedure which replaced cerebral fluid with air to improve the quality of brain x-rays.

In 1937, Bradley commenced his study with 30 residents of the Home diagnosed with behavioral disorders. Throughout the three-week study, a nurse observed each child closely. During the first week, the children were not administered any drugs. In the second week, the children were given a dose of Benzedrine each morning. In the third and final week, the drug was withdrawn.

The drug did nothing for the headaches but had a miraculous effect on the children’s behaviour. It also seemed to instill in them a previously missing ‘drive to accomplish as much as possible.’ The kids were calmer, behaved better, were more focused and performed much better at school. The cognitive improvements reinforced the results SKF had obtained from a trial the preceding year at a New Jersey detention facility for delinquent boys. That trial had demonstrated verifiable improvements in standardized test scores.

Bradley expanded his trial to 100 children in 1941 and the results were undeniable. Amphetamine appeared to ‘cure’ behavioural disorders in children but only for as long as they were taking the drug. As soon as they stopped, the behaviour reverted. There was no residue effect. It was not so much a cure as a very effective daily treatment. Bradley felt it was a useful supplement to his primary approach, removing the sources of stress from the child’s surroundings, which his own data told him did produce long term effects.

SKF had been looking for a mass market for amphetamine. The New Jersey study suggested that market might be school kids looking to improve academic performance. But reports were starting to appear suggesting people were becoming addicted to Benzedrine with some suffering psychotic episodes as a result. People had begun to realise that they valued the Benzedrine’s stimulant effects more than a clear nose. They started prying open the inhaler and either eating or injecting the amphetamine. It was clear that selling amphetamine to school kids was not going to be the mass market they were after and selling them to Bradley’s hyperactive kids was even less appealing. Luckily for SKF’s bottom line, the Japanese brought the US into the Second World War on December 7, 1941.

By 1942, substantial orders were being placed with SKF by the US Military, as it became evident that amphetamine was highly beneficial against combat fatigue or what we now call PTSD. The drug dramatically altered the way soldiers performed their duties, instilling confidence and purpose in individuals who might have otherwise shown fear or anxiety. The US Military handed out Bennies (Benzidrine tablets) like lollipops and SKF made money hand over fist. Any thought of marketing amphetamine as a treatment for rambunctious kids faded into the background.

Amphetamine would not be used as a regular treatment for “misbehavior” until the 1950s, when psychiatrists began to focus on the specific behavioral disorder of that by then had been christened ‘hyperactivity.’ Bradley’s successor at the Home, Dr Maurice W. Laufer, rediscovered Bradley’s work and by 1956 the profession was again using amphetamine and related stimulant drugs, like the newly released Ritalin – named after the discoverer’s wife, Rita – to improve the behavior of hyperactive children.

The idea of giving stimulants to kids who were bouncing off the walls was certainly counterintuitive, and the doctors had no clue why the drugs calmed them down, but there was little doubt that they did. And so by the 1960s, amphetamine and its ilk became a mainstream treatment for hyperactivity.

Why were amphetamine and other stimulants so effective? The answer only become clear within the last few decades. Those drugs increase dopamine levels and dopamine helps us focus. It stops our brains jumping from thought to thought in the haphazard way that we now suspect drives hyperactivity.

Have you ever struggled to get to sleep because your mind is racing? You jump from one thought to the next as an overwhelming sense of panic and urgency surges through your brain. Now imagine you have that feeling all the time. This is your brain telling you don’t have access to sufficient dopamine to allow you to focus. And this in turn leads to difficulties in concentration, impulsivity, restlessness, memory lapses. Managing time, emotions, and social interactions will be an ongoing challenge. When we are low on dopamine, we cannot remain focused on anything for more than a minute without our thoughts jumping the rails. If our brain came with a dashboard, at this point the ‘Low Focus’ light would be flashing red.

We need dopamine to stay focused. But the amount we need is determined by how frequently we are exposed to dopamine surges. Dopamine is the neurochemical which motivates us to run towards rewards and away from danger. But we develop resistance to it in highly rewarding or dangerous environments.

We need dopamine to stay focused. But the amount we need is determined by how frequently we are exposed to dopamine surges. Dopamine is the neurochemical which motivates us to run towards rewards and away from danger. But we develop resistance to it in highly rewarding or dangerous environments.

The kids being admitted to Dr Bradley’s Home were growing up in high danger surroundings. They were stressed by family alcoholism, poverty and abuse. They were receiving constant dopamine hits and their brain’s coping mechanism was to develop resistance to dopamine. This lowered the degree to which constant stress would affect them, but it also impaired their ability to focus.

Normal levels of dopamine were no longer enough for those kids. They were acclimatized to an environment where dopamine was constantly being spiked by stress. To just feel normal, they needed large amounts of dopamine. To the outside world that looked like the ‘rambunctious’ children Bradley encountered. They couldn’t focus. They had poor impulse control. They were reactive and irritable. And they couldn’t stay on task – any task.

He didn’t know it at the time, but when Bradley gave those kids amphetamine, what he was actually doing was providing them with dopamine stimulators. He could have achieved the same results with cocaine (popular with the British military), methamphetamine (popular with the German military) or heroin. For as long as the drug was in their systems (about 4 hours) the kids’ dopamine levels were boosted and they could behave and focus like other kids.

It wasn’t a cure for anything. In fact it could actually make the problem worse over time because the dopamine hits from the drugs would just increase the dopamine resistance. This is why people became addicted to Benzadrine. But Bradley’s trials did show that the drug could be used as a temporary treatment as long as the underlying cause, chronic stress, was being addressed.

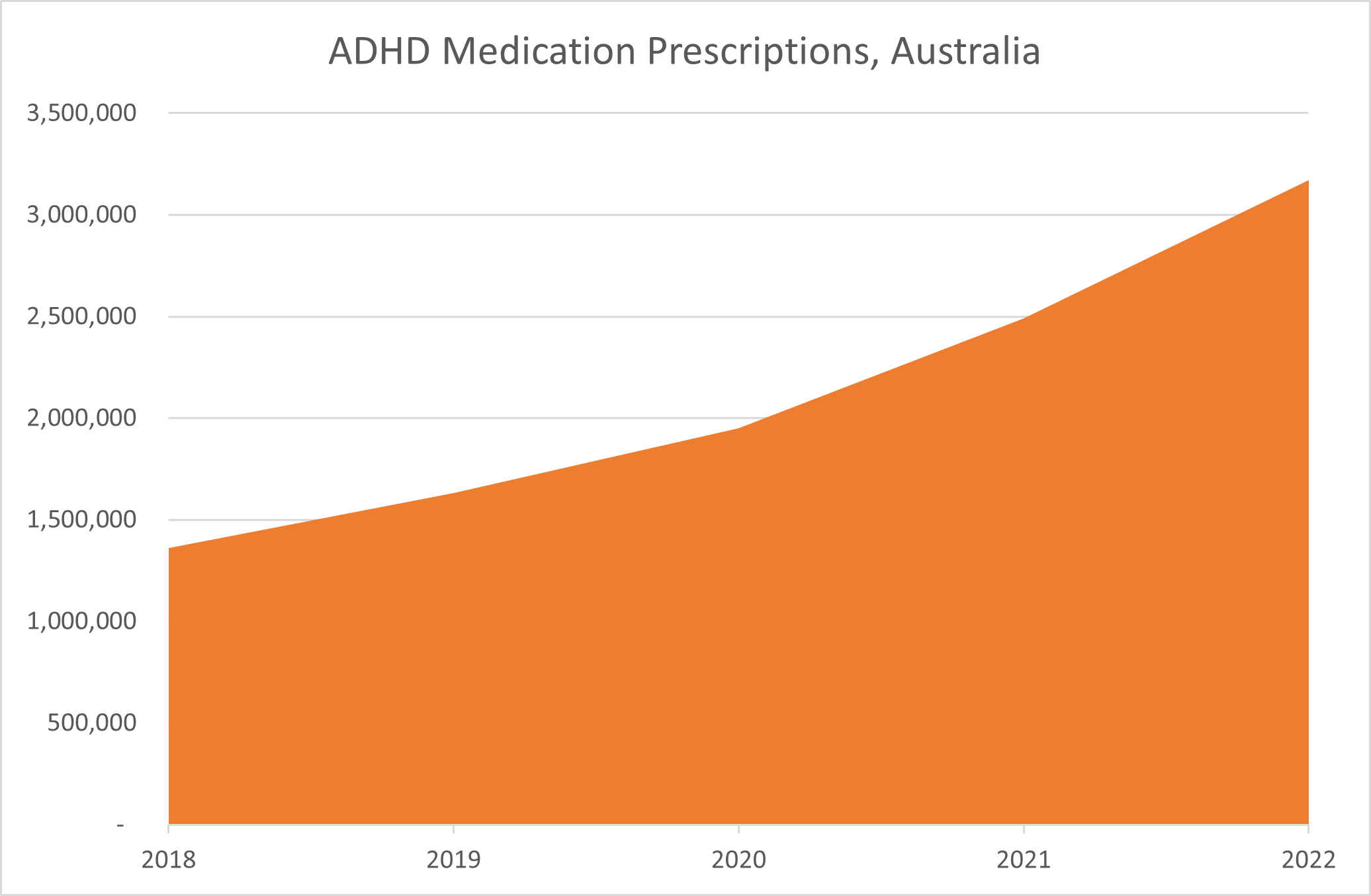

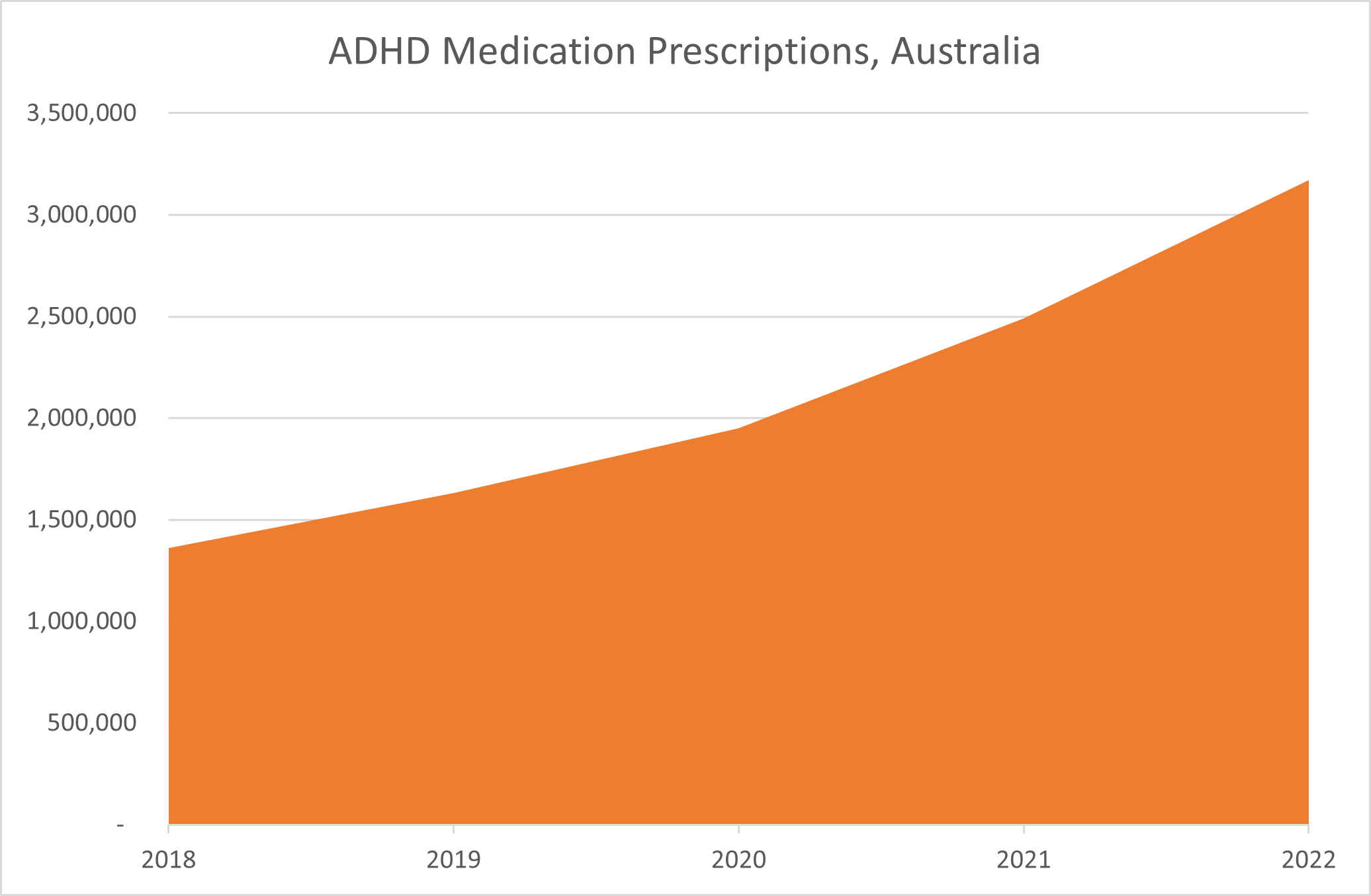

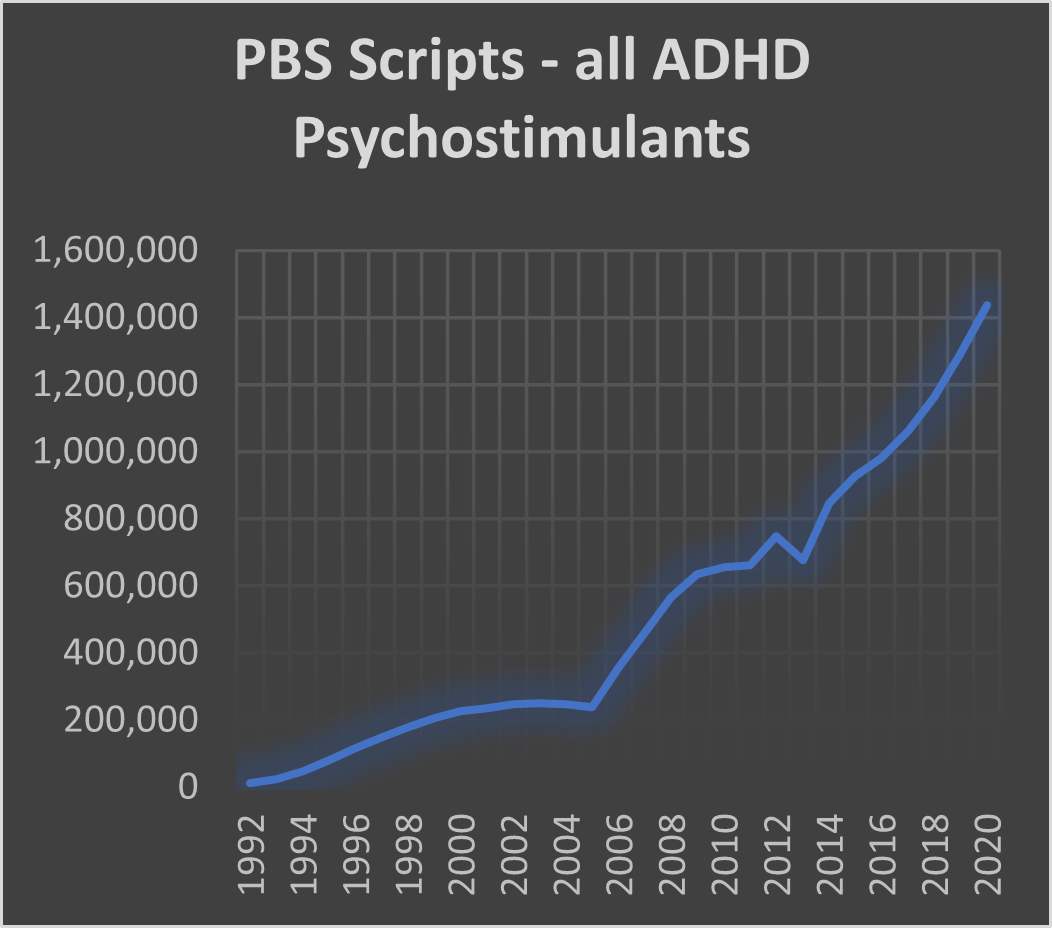

The ‘rambunctious’ kids Bradley was treating would today be diagnosed as having ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder). According to data revealed this week by the health department, over the past five years the number of Australians receiving prescriptions for ADHD medications has more than doubled. A total of 3.2 million prescriptions were dispensed in Australia during 2022. This represents a massive rise over the 1.4 million prescriptions written in 2018.

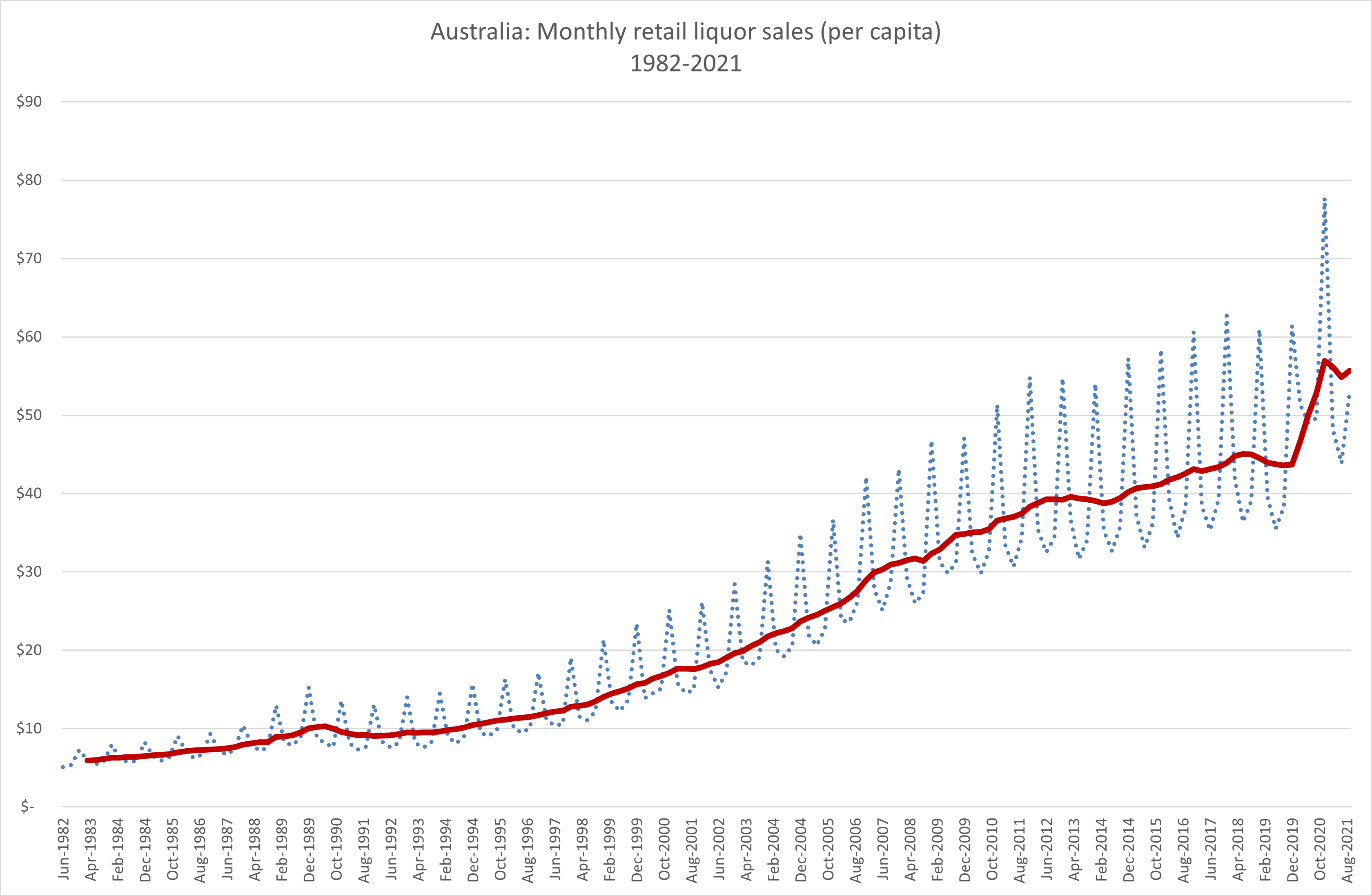

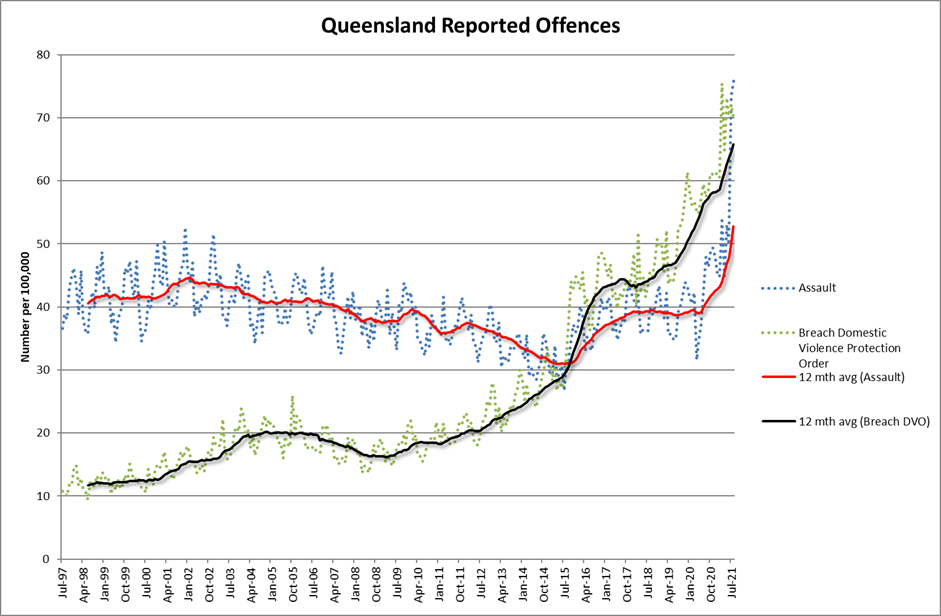

Surely modern-day Australia is not so much more stressful than the Great Depression or the Second World War. Why do we suddenly need to prescribe massive amounts of stimulants? The answer is that dopamine stimulants are both a cause and a treatment. Dopamine resistance is not only created by chronic stress. Chronic exposure to dopamine stimulants does the trick too. This is what was causing the addiction and psychosis among the Benzedrine sniffers. Modern day Australia is not as stressful a place as Depression era Australia but it does have unprecedented access to stimulants.

Surely modern-day Australia is not so much more stressful than the Great Depression or the Second World War. Why do we suddenly need to prescribe massive amounts of stimulants? The answer is that dopamine stimulants are both a cause and a treatment. Dopamine resistance is not only created by chronic stress. Chronic exposure to dopamine stimulants does the trick too. This is what was causing the addiction and psychosis among the Benzedrine sniffers. Modern day Australia is not as stressful a place as Depression era Australia but it does have unprecedented access to stimulants.

We can no longer buy amphetamine over the counter, but every time we smoke a cigarette, have a drink, or consume some of the less legal stimulants like speed, meth, heroin or opioids, we are stimulating dopamine and adding to our dopamine resistance. But we can also do it without ingesting anything. Every time we place a bet, watch porn, play an online game or interact with social media we are doing it too.

No, most of us probably aren’t the victim of the chronic stressors suffered by Dr Bradley’s Depression era kids, but we are likely to be getting even more dopamine hits in a typical day. And we are likely to be getting them from the phone we carry around in our pocket. The reason ADHD medication usage is exploding is that many, many more of us need the dopamine hit it provides, just to let us feel normal. The only way we can focus at all is when we have continuous access to high levels of dopamine stimulation. Ironically, as Dr Bradley observed at the dawn of the ADHD drug revolution, that is not a cure for anything if we don’t also address the underlying problem.

In Dr Bradley’s day the long term fix was to remove the chaos from the kids’ environment so as to allow their dopamine system time to reset. In our day it is that, plus removing the cloud of dopamine stimulants pouring from everybody’s phone. Our dependence on stimulant medication is a warning. The number of us now needing it just to live a normal life is accelerating wildly. But it will not cure anything, it just gets us through the day. If want a different outcome, we need to start acknowledging the cause of dopamine resistance and immediately acting to stop it. It’s time for phones to become once again, well, just phones.

Recent Comments