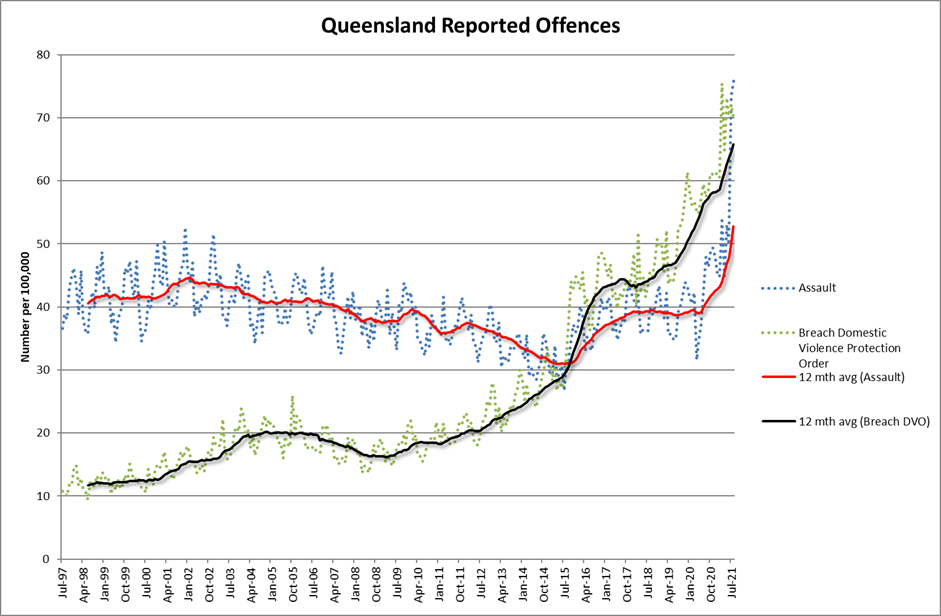

Queensland experienced the largest number of assaults ever in August 2021 according to data published by the Queensland Police. Last month there were almost 4,000 assaults in the State. This is double the number which occurred in August 2019. Similarly there were 37% more breaches of domestic violence orders in August 2021 when compared with August 2019. Blowouts like this do not happen in crime statistics. A bad year is a 10% increase. Something very, very odd is happening and the science says that COVID could be the culprit.

Studies in animals and humans tell us our mental stability is driven by dopamine signalling. Too many dopamine hits too often will lead to mental illness as certainly as night follows day. We are most familiar with this when the thing delivering the hit is a stimulant drug like cocaine or meth. But we can also get those dopamine hits by experiencing stress. Just as dopamine motivates us to chase rewards, it is also used to make us respond to danger. Same system, same neurochemical, same result. We end up in an on-edge state either anticipating reward or danger. Both pleasure and pain deliver the same dopamine surge.

Studies in animals and humans tell us our mental stability is driven by dopamine signalling. Too many dopamine hits too often will lead to mental illness as certainly as night follows day. We are most familiar with this when the thing delivering the hit is a stimulant drug like cocaine or meth. But we can also get those dopamine hits by experiencing stress. Just as dopamine motivates us to chase rewards, it is also used to make us respond to danger. Same system, same neurochemical, same result. We end up in an on-edge state either anticipating reward or danger. Both pleasure and pain deliver the same dopamine surge.

The strength of that hit is significantly accelerated by uncertainty. Continuous exposure to addictive substances delivered on an uncertain schedule pushes us into a state of anxiety and depression. And in exactly the same way, continuous exposure to uncertain danger does the same. If our housing is not certain. If our food is not certain. If our job is not secure. If we could catch a deadly disease just by going to the shops. If we’re trying to work from home and home-school. If we don’t know if we will be in lock-down tomorrow, we are in a constant state of on-edge preparedness for danger.

Our brain turns uncertainty-boosted dopamine hits into a semi-permanent change to the brain biochemistry that helps us cope with our high-dopamine environment. Unfortunately, that coping mechanism comes at a cost – our mental health.

Dopamine-adapted brains are anxious. They overreact, are irritable, have low impulse control, have weak memory and make poor decisions without care for consequences. If we allow that mental state to go on indefinitely, we place ourselves and others at mortal risk from self-harm, domestic violence, or suicide. It is meant to be a temporary adjustment, not a permanent state.

One of the most studied areas of impulsivity is domestic violence. A long line of studies have established that about two-thirds of recorded instances of domestic violence are impulsive. We would therefore expect that anything likely to raise the level of impulsivity, such as stress or addiction, would also raise the level of domestic violence. The data makes it clear that the two are very closely related.

A major US study of over 23,000 demographically representative households found that women in more disadvantaged neighbourhoods were more than twice as likely to be a victim of domestic violence when compared to advantaged neighbourhoods. Digging a little deeper, the researchers found that the rate of violence jumps from 4.7 per cent when the male is always employed to 7.5 per cent when he experiences one period of unemployment. If a man from a disadvantaged neighbourhood has continuous unstable employment, the rate jumps to 15.6 per cent.

The higher the level of financial uncertainty, the higher the level of domestic violence.

Similar research in Australia based on 13,375 households revealed similar correlations between stress and violence. The Australian study found that the risk of family violence was three to four times as high in households suffering financial stress, jumping on average from around 4 per cent to nearly 15 per cent. This was after controlling for age, parental status and drug dependency.

The dopamine tolerant state induced by chronic stress will drive someone to seek addictive substances. Accessing Cocaine, Nicotine and Booze, Porn, Social Media and Gambling are all stress relieving behaviours. But they all make things worse. They temporarily reduce anxiety quickly and effectively, but because they also deliver a dopamine hit, they ultimately make the dopamine adapted brain even worse. Alcohol is often the first port of call to cope with stress.

Commonwealth Bank card spending data tells us that Australians spent between 30 and 45% more on alcohol in 2021 than they did in the same months in 2019.

It provides a temporary solution, but it also significantly reduces inhibition and impulse control and gives people a sense of invincibility. A community infused with high levels of drunkenness will be one in which violence and crime occur at significantly higher levels. And in turn the stress created by random acts of violence in the community will increase the likelihood of it occurring more often. It is a vicious cycle that rapidly accelerates, as clearly demonstrated in the stats from QLD police.

The really bad news from those stats is that those crimes are seasonal. The worst months for assaults are December, January, and February. August 2021 may have set a record, but it is likely to be broken very soon.

COVID has created a wave of uncertainty that affects almost all of us, almost all of the time. For as long as that uncertainty continues, these crime statistics will rapidly spiral into territory none of us has ever experienced. Governments must recognise this urgently and plan to provide the financial and social certainty we all desperately need. Because if they don’t the society we think we know will tear itself apart in a stressed, addicted and impulsive rage.

Photo by RODNAE Productions from Pexels

Recent Comments